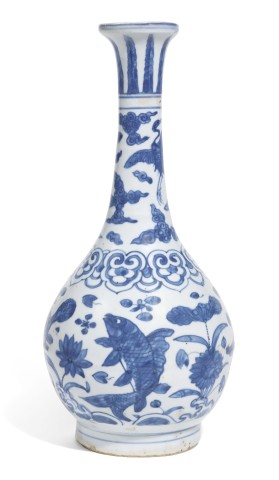

The pear-shaped body raised on a straight foot, the long tapering neck with flaring mouth rim, boldly painted to the exterior with a lively design of fish swimming in a lotus pond with waterweeds and aquatic plants; the four fish include black carp, red fin culter, silver carp, and Chinese perch, the names of the fish in Chinese combine to form the rebus qingbai lianjie, 'of honourable descent and incorruptible'; the neck decorated with two cranes flying among stylised clouds above a wide band of ruyi-heads, with upright lappets around the mouth; the base with a four-character mark reading Wanfu youtong (May infinite good fortune be bestowed upon you).

Literature

For a vase with similar form, see the British Museum (museum number PDF.689), attributed Jiajing (1522-1566), and the Metropolitan Museum (museum number 16.61), attributed Wanli (1573-1620).

Objects painted with bold designs of fish swimming in lotus pools are unusual, but enjoyed popularity buoyed by support from Emperor Jiajing, a devout Daoist, who had a preference for designs with auspicious meaning, and as such Jiajing works are often brimming with Daoist symbolism. In Chinese, the word for fish (yu) is a homophone for abundance and affluence. The carp is associated with freedom, wealth, and advancement in official life. Fish swimming together in a pond creates the rebus jin yu man tang, ('May your hall be filled with gold and jewels'). The crane is a symbol of longevity, and is regarded as a 'bird of the first rank'. On this vase, the cranes are flying; flying cranes are said to represent a desire to rise up among official ranks. They are also thought to transport the Daoist Immortals to heaven.

In 1551, the 30th year of the Jiajing reign, the Imperial court commissioned 200 blue and white vessels painted with fish, reflecting the Emperor's love of auspicious designs. A record of this can be found in the Tao shu (Book on ceramics) of the Jiangxi gazetteer (Jiangxi sheng da zhi). However, this shape of vase with this design of four different fish appears to be rare. Moreover, the naturalism of the fish on this vase, with different breeds clearly described, is impressive, considering the challenges involved in observing fish swimming in their underwater habitat.

Fish swimming in a pond is a motif associated with a passage in Zhuangzi by the Daoist thinker Zhuang Zhou (c. 369-c. 286 BC). In this passage, he opposes the free movements of fish with the logical reasoning of the Confucian Huizi. Ultimately, Daoist spontaneity wins out against the restrictive methodologies of Confucianism. The 'Pleasures of Fishes' became a euphemism for unrestricted freedom. For the Chinese literati, who lives were bound by bureaucracy, the 'Pleasures of Fishes' became an unattainable ideal. The Daoist celebration of spontaneity is reflected in the painting of this vase. The fish are expressively depicted swimming about in dynamic poses, among freely painted water plants, with additional movement lent to the composition by the waves crashing around the base.