BE38

Further images

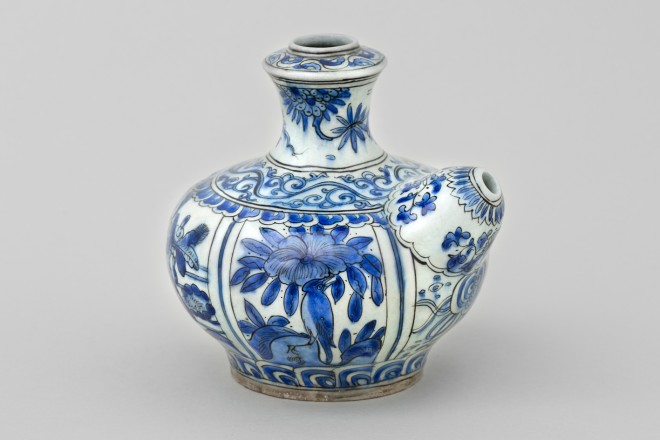

Of stout, globular form, with a concave neck and mammiform spout; the decoration in imitation of Chinese export Kraak style, painted in underglaze cobalt blue, with outlines and fine details picked put black; the five lobed panels on the body filled with a variety of different birds and flowers, one with a crouching deer by a fence under a cloud, and the panel below the spout with a freely-painted ruyi-head surrounded by ribbons, all set between key-fret pattern borders; around the shoulder, a band of scrolling tendrils outlined with two thin black lines; on the neck, a bird perches on a flowering branch, the mouth rim with a band of leafy scrolls; the spout similarly decorated with floral sprays, and a petal-like border around the mouth; the base glazed, painted with a pseudo-Chinese character.

Literature

A similar, dated example is in the collections of the V&A (V&A 592-1889), dated 1051 A.H. (1641 C.E.). The dated one is of the same form, and the central panel with a deer is almost identical to ours.

In Iran, blue and white ceramics such as this kendi were mainly produced during the Safavid Dynasty, from the early 16th century to the early 18th century. During the Ming dynasty (1368-1644), kendi were produced in Jingdehzen for export to Central and South East Asia. There is an example of these Chinese originals in the Victoria and Albert Museum (museum number C.570-1910). Another Chinese example in the Kraak style, was purchased in Iran from the Richard collection (V&A, museum number 1564-1876).

The Chinese models were replicated and produced by Persian potters for a short time. As such, Safavid kendis can be confidently dated to the second quarter of the 17th century according to Crowe (2002). Although there were pre-existing ceramic styles in Iran, Safavid potters became particularly interested in replicating Chinese blue and white porcelain, and by the 17th century this had become the dominant style.

Chinese porcelain had been imported into Iran as early as the 1580s. By the 1620s Iranian potters could produce convincing imitations of Chinese imports. However, crafting Kraak-style designs on vessels with thin walls presented a particular challenge. Also, the characteristic underglaze cobalt blue used for Safavid ware is fugitive during the firing process and so tended to run. To counter this, Iranian potters developed a method, which was later copied by the Dutch, of outlining the designs in manganese black to emulate the sharp detail of the original Chinese designs.

For an example of a Safavid spouted form like this one and painted in the Kraak style see, Arthur Lane, later Islamic Pottery published by Faber and Faber 1971, plate 79, page 97 This shape derived from the Chinese vessels, kendi, which were used for drinking or pouring, the Persians adapted and used for smoking and they became ghalian bases.

This kendi or ghalian base would have been made in Mashhad according to research done by Chardin,Lane and others.

With the closing of the Chinese market in 1659, Persian ceramic soared to new heights, to fulfil European needs. The appearance of false marks of Chinese workshops on the backs of some ceramics marked the taste that developed in Europe for far-eastern porcelain, satisfied in large part by Safavid production. This new destination led to wider use of Chinese and exotic iconography (elephants) and the introduction of new forms, sometimes astonishing (hookahs, octagonal plates, animal-shaped objects).

Similar examples exist in the Victoria and Albert Museum, London, Museum numbers: V&A 1076-1876; V&A 430-1878; V&A 998-1876.

For reference, see:

Persia and China: Safavid Blue and White Ceramics in the Victoria and Albert Museum, 1501-1738, Thames & Hudson, Geneva, Switzerland and London, cat. no. 118, pp.99-100

Golombek, L., Mason, R.B., Proctor, P., Reilly, E. (2013) Persian Pottery in the First Global Age: The Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries. Brill, Leiden, p. 47.