This should be read in conjunction with our catalogue.

In recent years the porcelains of the 16-18th century have been the subject of much scholarly attention. In London in 1994/5 a joint exhibition of 16th century ceramics was shown by the British Museum in association with the Oriental Ceramic Society, and an exhibition entitled Ceramic Evolution in the Middle Ming Period was held at the Percival David Foundation in collaboration with the Victoria and Albert Museum, for which a catalogue with bilingual captions was produced.[1] A one-day symposium was also held at the British Museum, at which a number of scholars discussed their recent research. In New York in 1995 the China Institute held an exhibition entitled Chinese Porcelains of the Seventeenth Century, which was accompanied by an excellent catalogue by Julia B. Curtis,[2] with an essay by Stephen Little. Little was also among those who contributed essays to the catalogue of the exhibition Seventeenth-Century Chinese Porcelain, which began a tour of American museums in 1990.[3] In addition, a number of the scholars speaking at the Percival David Foundation colloquy on The Porcelains of Jingdezhen in 1992 addressed aspects of porcelain production in this period.[4]

If these exhibitions, scholarly writings and symposia have furthered our understanding of the technology, changes in patronage and meaning of the decorative motifs on these ceramics, the material brought to light through terrestrial and maritime archaeology has provided us with new shapes and designs as well as a firmer base from which to attempt dating of related wares. Among the most significant of these archaeological finds are those from the site of the imperial kilns at Jingdezhen. While the finds from the 14th and 15th centuries have received the most attention, some of those from the later Ming reigns have also been of considerable importance. The discovery, for instance of a number of sherds of kraak wares in the Wanli-Tianqi strata at Zhushan, Jingdezhen[5] has disproved once and for all the notion that kraak porcelain was not made at Jingdezhen, in the same way that its earlier discovery in a Chinese tomb disproved the idea of it being solely an export ware. Another, very significant, find was, of course, the tablet excavated from the site of the Ming Imperial Factory at Zhushan, Jingdezhen and dated by inscription to the 10th year of the Chongzhen reign (AD 1637). This tablet bears a long inscription, but there are two sections which are of special importance. These may be translated as reading:

"... During the Wanli reign administration of the factory was again imperially asigned to a eunuch official. In the 36th year of his reign (AD 1608), when production ceased, the eunuch official was again recalled."

Later the text continues: "...Today the eunuch officials are no longer sent ... there are now no activities in the factory."[6]

Here then we are given a firm date of AD 1608 for the cessation of production at the Imperial kiln, and it is confirmed that oficial production was still suspended in AD1637. It was to remain so until the whole kiln complex was reorganised under the Kangxi emperor of the Qing dynasty.

Much has also been learned from the products of maritime archaeology. The cargo of the Witte Leeuw (White Lion), which went down in the harbour of St. Helena in AD 1613,[7] and that of the Banda, which sank off the Mauritian coast in AD 1615,[8] may be seen in conjunction with the material found at Drakes Bay in California, which is believed to have come from the Drake and Cermeño expeditions of AD 1579 and 1595.[9] To the information from these finds has been added the material from the so-called "Hatcher" wrecks. The first of these was the VOC vessel, which went down in the South China Sea in the 1640s. The cargo from this wreck was sold at Christie's Amsterdam in March and June 1984, and its history was researched by Christiaan Jörg for his cataolgue of the exhibition at Groninger Museum.[10] This cargo, which contained porcelains of late Ming and Transitional type was of particular importance, since unexpected shapes as well as decoration were found. The excavation by Captain Hatcher of the Geldermalsen, another VOC ship, this time dated to AD 1752, added to our knowledge of mid-18th century export wares.[11] More recently the so-called "Vung Tau Cargo", from a ship that foundered off the coast of Vietnam on its way to Batavia in about AD 1690, shows, as the introduction to the Christie's sale catalogue points out, how well the porcelain industry had recovered after the strife connected with the change of dynastic rule.[12]

Various aspects of form and design are highlighted by the Vung Tau cargo. A number of the forms are enhanced with spiral lobing, which often appears to have been taken into little account when the decorator covered the vessels with dense floral scrolls. In actuality, closer examination of vessels such as tall lidded jars[13] reveals that the flowers are rather carefully placed to complement the lobing without seeming to be subservient to it. A number of these vases, like the pair in the present exhibition (no. 27) have an additional petal band around the base of the body. Another feature seen on these and the Vung Tau pieces is a banding and articulation where the body and foot meet. Such raised banding at this point is also a feature of other shapes such as the high-footed cups seen both in the c.1690 cargo[14] and the current exhibition (no. 24). The stand with the latter cup has a multiple-petal form, and this too is seen in a number of other shapes including a pair of large bowls with bracket-lobed rims (no. 32) and a single blue and white bowl (no. 33, below), and the covered bowls from the wreck.[15] Multiple petals appear around the base of several forms, sometimes combined with vertical panels as in the case of the wall vase (no. 37).

33. A FINE AND LARGE BLUE AND WHITE MOULDED FLARING BOWL, KANGXI (1662 - 1722)

Wall vases with flattened backs became popular in the 16th century, and indeed are mentioned in the 1597 edition of the Jiangxi sheng Dazhi (Jiangxi province gazetteer), where it is recorded that 400 blue and white wall vases were ordered for the court in 1592.[16] The form continued to be produced in the Qing dynasty, being decorated not only in underglaze cobalt blue but also in overglaze enamels. An example of the latter, made to hang in an imperial sedan chair, is in the Percival David Foundation and bears a long inscription composed in AD 1742 and applied on the instructions of the Qianlong emperor.[17]

Like wall vases, porcelain garden seats decorated in fahua-style on-biscuit enamels and underglaze blue became popular in the middle Ming period (280 were ordered for the court in 1584[18]). They continued to be manufactured into the late Ming and Qing, when some of them were made from highly refined raw materials and were elegantly decorated. The Qianlong seat (no. 39) is a good example, being typically drum-shaped, and having retained the raised bosses indicating drum-nail heads that are a feature of both underglaze blue and fahua examples in the early 16th century. The decorative piercing, here seen around the double cash motifs, was also seen on Ming examples,[19] and is functional, allowing a circulation of air to keep the seat cool in summer.

Garnitures composed of tall covered jars and vases in simplified gu-beaker form were particularly popular in the Kangxi period. One varient that owed little to the early bronze form was the facetted shape (no. 23). Combined with appropriate panelled decoration this could be most effective. Facetting, particularly to provide an octagonal plan can be seen applied to a wide range of forms - not only elegant garnitures, but also more utilitarian cups and saucers.[20] Even where the actual form is not facetted, the simplified gu-form was sometimes painted with vertical panels, although with detailing at mouth and foot, as in the well-painted example (no. 36, below).

36. A BLUE AND WHITE GU-FORM VASE, KANGXI (1662 - 1722))

Horizonal banding was introduced into the decoration of closed forms in China at least as early as the Song dynasty.[21] A particular feature of late 17th century design, however, was to divide the form into the normal bands at foot and shoulder, reserving the dividing zone in white except for simple fine lines around the vessel. Instead of having different motifs in each of the bands, as was usually the case on earlier wares, the same dense floral scroll was painted in each register. This can be seen in traditional divisions, but with added vertical ribbing, on two covered vases (no. 38), or with an additional reserved dividing zone mid-way between the other two as on some Vung Tau garnitures.[22]

Although many traditional Chinese shapes, like covered jars, flourished throughout the period and were made for both domestic and export market, special forms were also made for certain groups of foreign patrons. First it was special designs that were painted on the porcelains for overseas clients, initially a few armorial pieces for the Portuguese, and later a wider variety of decoration for the Dutch of the VOC. Then the forms themselves were adapted or specially introduced for foreign trade. The Dutch traders had established themselves at Fort Zeelandia on Taiwan in 1624,[23] and from there were able to exert more influence on the porcelains made for them. In 1635 an order was issued by the VOC requesting new and interesting shapes to be produced from supplied wooden models.[24] From this time onwards a range of European forms appeared among the blue and white porcelains produced at Jingdezhen, the most usual being the wide rimmed plate known as a klapmutsen, after an item of Dutch headgear, and beakers.

A wide variety of foreign shapes were made in blue and white in the succeeding years, less common forms including salts (no. 34) and pieces like the writing set (no 28). The latter is a charming example of the happy combination of Chinese and European design. The stand itself is well within Chinese traditions, while the inkwell, sand shaker and pen holder are strictly the preserve of the European writer not the Chinese calligrapher. A less aesthetically pleasing but no less interesting example of East meets West can be seen in the vases (no. 25), which appear to be an ungainly transference of an Italian glass form into painted porcelain. One reason for the strange quality of these vases may have been that they were not well copied by the Dutch when producing the wooden models from which the Chinese potters were expected to work. The suggestion that they were made for the Dutch market is supported by the fact that an example is in the Princessehof Museum in Leeuwarden, although other examples found their way into the collection of the Ottomans in the Topkapi Saray, Istanbul.[25]

Not only did the cessation of production at the Imperial Ming kiln in 1608 necessitate a concentration on wider markets, both at home and abroad, on the part of the Jingdezhen potters, it also freed them from the dictats of court taste in terms of the motifs that should be painted on porcelain. The result was a blossoming of designs and decorative schemes. One of the most interesting areas of decoration in the 17th century was that concerned with the depiction of literary, historical and religious figures.

In some cases we can recognise these figures relatively easily, either because the vessels on which they are depicted bear inscriptions that provide direct or indirect clues to their identity, or because the stories from which the characters derive are still popular today. In other cases it is much more difficult to find the source of particular individuals or groups of figures. In the Qing period we become increasingly accustomed to seeing Europeans depicted on Chinese porcelain, however western figures and themes do appear on some late Ming vessels. There is an interesting group of large kraak dishes (c. 50 cm. diameter) and large kraak bowls (c. 36 cm diameter) dating to about AD 1640,[26] which contain a mixture of Chinese and western themes. The cavetto and rim of the dishes and sides of the bowls are divided into alternating wide and narrow panels. In some cases two of the wider panels contain scenes of figures in landscape, as in the case of dishes in the Percival David Foundation[27] and the Groninger Museum,[28] in some cases three as in the case of the bowl in the De Sypesteyn Museum, Loosdrecht,[29] and in some cases four of the wider panels have scenes of figures in landscape as can be seen on the dish in the current exhibition (no. 7). Usually, but not invariably, it is a single figure of a Chinese fisherman, birdcatcher, reedcutter or farmer carrying his line, nets, prey, tools etc. on a pole balanced on his shoulder. The other panels, both wide and narrow are filled with floral elements in a very specific style, and which includes depiction of tulips and carnations. The way that these flowers and leaves are painted, as well as the minor concentric bands, contains echoes of both European Rennaissance and Near Eastern design, but have no predecessors in the Chinese decorative vocabulary. It should be remembered that although tulips are indigenous to Turkey and both tulips and carnations appear on Turkish Isnik wares of the 16th century, tulip cultivation had become a major preoccupation in the Netherlands by the 1630s. Christiaan Jörg has found a VOC document sent from Batavia to Fort Zeelandia (Taiwan) in 1639 instructing their buyers to obtain porcelains decorated with "Dutch flowers", probably a mixture including carnations and tulips.

In cases such as the dish in the current exhibition, the central area contains a well-composed traditional Chinese design of figures in landscape. In this instance a figure kneels in front of a scholar-offical and his attendant on what looks to be a road through the mountains. The figures in the radiating panels are fisherman and farmers. In complete contrast, the Loosdrecht bowl has in its central panel a landscape showing European (probably Dutch) houses and a river or canal with ducks. Of the three large pictorial radiating panels, two contain two large Chinese figures in a landscape with European buildings, while the third is dominated by European buildings with two small Chinese figures.

The David Foundation and Groningen dishes have very similar compositions in their central panels. They depict two figures dressed in Persian style. The figures are seated on the ground, one leaning against a rock, with flowers in the foreground and a shrub to the right of the figures. It has been suggested that the scene was painted, albeit in a somewhat debased manner, after the style of the famous Persian painter, Riz_ cAbbasi (active AD 1598-1643). The David and Groninger dishes differ slightly in their radiating panels. Both have two panels depicting bird-catchers with birds hanging from either ends of their poles, however in the other four wide panels the David dish has tulips in the same western style as is seen in the narrow panels, whereas the Groninger dish has two tulip panels, and two panels with large-scale sprays with peach-like fruit and multiple tiny leaves. Thus, within this one group of bowls and dishes we can see elements from three distinct cultures: Chinese, European and Islamic. Interestingly, the VOC specifically requested porcelains decorated with Chinese figures,[30] but it is likely that most Europeans in the seventeenth century would have been unable to differentiate between Chinese and Persian dress.

Many figures from the Daoist pantheon appear on Chinese ceramics. The most famous of all are the Eight Immortals, who appear on porcelain as early as the Yuan dynasty and become increasingly popular in the 16-18th centuries. The Eight Immortals are a mixture of mythological figures and recorded historical figures from different periods of Chinese history. They may be shown singly, in small groups, all eight together, all eight with the Star God of Longevity, or they may simply be suggested by the depiction of the Eight Daoist Emblems, which are made up of the attributes associated with each of the Eight Immortals. Certain aspects of Daoism are also associated with magic, and different manifestations of this can also form part of the designs on porcelain.

6. A BLUE AND WHITE SAUCER DISH, JIAJING (1522 - 1566)

A dish in the current exhibition (no. 6, above) depicts three of the Eight Immortals together with a jar from which issue magic spells, and a long-tailed turtle (symbolic of longevity/immortality). The immortal seated on the left is Lu Dongbin, who is shown with a magic sword on his back, which was given to him by the Fire Dragon. He is supposed to have been born in the 8th century in Shanxi province and to have followed in the footsteps of his father and grandfather serving as on official, before meeting another of the Eight Immortals, Zhongli Chuan under whose influence he gave up his career, went to live in the mountains and became an immortal. Zhongli Chuan himself is shown on the right standing beside the magic jar. Various legends attach to him, but he is sometimes known as Han Zhongli, having been born in the Han period. He is usually depicted as a military figure and carries a fan, shown here behind his shoulder. The central figure is Cao Guoqiu, who can be identified by the jade tablet for admission to court resting against his knee, which is symbolic of his connection with the Song imperial family. He is also shown with leaves in his hair, a reference to the fact that as penance for dreadful deeds he abandoned his official position and lived as a hermit, clothing himself with wild plants.

As mentioned above, the other figure frequently depicted with the Eight Immortals is the Star God Shoulao, the God of Longevity. He also appears with two other Star Gods, of Rank and Happiness, as on the rouleau vase (no. 35). Shoulao (or Shouxing) is shown as an old man with high-domed forehead and benign smile, holding a peach, leaning on a staff and accompanied by a crane and a spotted deer. In this grouping, however, the deer may be associated with Luxing since deer and rank are both pronounced "lu" in Chinese. Luxing, the Star God of Rank, is shown dressed as an official and carrying the jade tablet that allows admittance to court. Fuxing, the Star God of Happiness, is usually shown with a small boy, who can be seen as symbolic of the happiness of having sons. More specifically, if Guo Ziyi is identiified as the God of Happiness, then the little boy is his son Guo Ai, who he is taking to the court. These three Star Gods are a very popular theme on porcelains of the early Qing, where they are often accompanied by [red] bats, which in Chinese provide a homophone for happiness or blessings. The figures may also be depicted under or beside a pine tree, which is a further symbol of longevity.

In a number of stories major historical figures are combined with mythological, often Daoist, figures. One that became very popular in the late Ming period relates to Emperor Xuanzong, whose reign title was Minghuang (AD 712-55). Xuanzong was completely besotted with his concubine Yang Guifei. When the An Lushan Rebellion began in 756 the emperor was impelled to flee to Shu (Sichuan) and at the beginning of the journey was forced to witness the strangulation of Yang Guifei by his imperial guards, who blamed her for the emperor's neglect of the empire. The emperor was heartbroken, and his grief was touchingly expressed in poem entitled Song of Eternal Sorrow by the Tang poet Bai Juyi (AD 722-846):

In the Ming dynasty plays based upon this poem became popular, although the version of the story that has come down to us is from an edition of AD 1688 entitled The Palace of Eternal Youth by Hong Sheng.[32] There are two versions of the story. In the original poem the spirit of Yang Guifei is eventually found by the emperor on Penglai, the isle of the immortals. In the version more often depicted on porcelain, the emperor, in his determination to be reuinited with Yang Guifei travels with his Daoist alchemist, Le Gongyuan, to the Guang Han Palace in the moon, the home of the goddess Chang E, in the hope of finding Yang Guifei's spirit. A small Wanli ewer in the Percival David Foundation was made in the shape of a flattened moon, resting on a bridge of clouds and with a cover in the shape of a cloud.[33] Figures are moulded on either side of the ewer. On one side is the moon goddess, Chang E, who stole the elixir of immortality from her husband, the archer Yi, and fled with it to the moon. She is shown beside the white hare who pounds the elixir, using a pestle and mortar, under a cassia tree. On the other side the emperor Xuanzong and his Daoist archemist are depicted. They are shown standing on the bridge of clouds across which they are supposed to have reached the moon. The little ewer is dated to c. 1600, the same date as a woodblock illustration entitled Tang Wang yu Yuegong (The Tang Emperor visits the Moon Palace), published in the Dabei duizong, which depicts both emperor and archemist in similar poses to those on the ewer, and also shows Chang E with an attendant and the white hare.[34] It seems likely that a book illustration similar to this one provided the inspiration for the scenes on the ewer.

The figures on a number of well-painted porcelains from the Transitional period come from the 14th century novel by Shi Nai'an entitled Shuihu zhuan (known in English as The Water Margin). From the mid-seventeenth century this novel was a popular subject for decoration on porcelain, in both underglaze blue and later in famille verte enamels. Early in the Chongzhen period an edition of the book was published with woodblock printed illustrations, and these provided the porcelain decorators with an excellent source of images. The story revolves around a group of heroic outlaws, who in opposing corrupt officials are forced to live in the area of Liang Shan Bo in Jizhou. They can, perhaps, be characterised as a Chinese equivalent to Robin Hood and his Merry Men. The stories are set in the Song dynasty, but were particularly apt in the late Ming period, when corruption was rife, the court was weak and local rebellions were frequent. Indeed the tales were deemed to be seditious, and by 1642 the novel was officially surpressed.[35] This in no way prevented its characters being used as decoration on porcelain. In some cases it is only possible to guess that The Water Margin might have been the inspiration for the decoration on a particular vessel, as on the finely-painted blue and white Chongzhen jar (no. 14). Here the warrior is not identified by an inscription and could be another hero from Chinese history or mythology. The opposite side of this jar is covered by particularly dramatic swirling clouds, but these do not help with identification of the scene as they are a popular decorative device in the mid-17th century.

44. A BLUE AND WHITE VASE, KANGXI (1662 - 1722)

44. A BLUE AND WHITE VASE, KANGXI (1662 - 1722)

A positive identification of characters from The Water Margin can, however, be made in the case of a Kangxi vase in the exhibition (no. 44, above), on which the two figures are named in the inscriptions written beside them. These inscriptions read:

"Using two iron whips is Huyan Zhuo's speciality"

and

"Wu Song lashed with a bamboo whip"[36]

General Huyan Zhuo was the grandson of General Huyan Zhan, and both were adept at a particular fighting skill using two barbed iron whips (called bian), one in each hand. One section of The Water Margin tells how the emperor was angered by the exploits of the Liang Shan Bo outlaws and commanded the Minister of War, Gao Jiu, to deal with them. Gao Jiu sent to Henan province for General Huyan Zhuo, who was duly appointed commander of the force to go and defeat the bandits and was presented with a black horse by the emperor. Huyan Zhuo's army was defeated by the Liang Shan Bo outlaws. In retreat the horse given to him by the emperor was stolen by another group of bandits from Dao Hua Shan. While trying to retrieve his horse, General Huyan Zhuo engaged three of these outlaws in single combat. They fought skilfully and bravely and he was unable to vanquish any of them. One of the outlaws he fought was Wu Song (the other figure identified on the vase), who had become a hero in the area when he killed a tiger with his bare hands. Wu Song and the other men from Dao Hua Shan joined forces with the outlaws from Liang Shan Bo in order to defeat Huyan Zhuo's troops. They decided that the best plan was to capture General Huyan Zhuo, which they did. Having taken him prisoner they treated him with respect and explained that they were not disloyal to the emperor but only in opposition to corrupt officials like the Minister of War. Eventually Huyan Zhuo agreed to join them and later to put their case to the emperor in the hope of their being granted imperial pardons.

24. A RARE TRANSITIONAL BLUE AND WHITE SAUCER DISH, SHUNZHI C. 1645-60

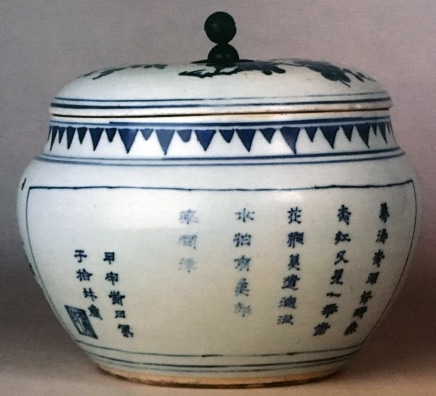

The decoration on a fine Shunzhi dish in the exhibition (no. 24, above) takes as its subject the same theme as that appearing on a covered jar (no. 2), which bears an interesting inscription dated AD 1644, the year that saw the suicide of the last Ming emperor Chongzhen, the establishment of the Manchu Qing dynasty and, in Nanjing, the installation of the first Ming pretender to the throne, Zhu Yousong (reign name Hongguang). The poem inscribed on the jar may be translated:

"Search in the peach grove for refuge; it provides sanctuary from the Qin,[37]

When the peach trees blossom, another spring will come.

Let not the blossoms float away on the flowing water,

Lest there is a fisherman who comes to ask the way [to Peach Blossom Spring].

Written on a spring day in Jia Shen [cyclical year equivalent to AD 1644] at the Shilin

Studio."[38]

The reference is to a story related by Tao Qian (AD 372-427) of a tranquil village known as Peach Blossom Spring, which exisited without the concept of time passing. In this tale a fisherman from Wuling sailed along a river without taking note of how far he had gone, and came upon a stretch where blossoming peach trees lined the banks:

"No tree of any other kind stood among them,

but there were fragrant flowers, delicate and lovely to the eye,

and the air was filled with drifting peachbloom"[39]

When the fisherman disembarked and went to look among the trees he found a spring and a cave going into the hillside. He entered the cave and walked through it to emerge on the other side into a prosperous village where:

"White-haired elders and tufted children alike were cheerful and contented".[40]

The fisherman left the village after a few days, intending to return later but was never again able to find the way.

On both the dish and the jar a sage is pointing to show a fisherman the way to the mythical village of Peach Blossom Spring. On the dish it is clear that the figures are standing in front of a cave, as the story requires, while on the jar the cave is merely suggested. On the jar the sage is accompanied by a single attendant, but on the dish two adult figures stand bending slightly forward and a little boy points with his toy windmill in the same direction as the scholar is indicating to the fisherman. The village itself appears in neither picture, but the branch stretching out from the cliff depicted on the dish is probably from a blossoming peach tree, like those which flanked the river bank in the original story.

The poem on the jar refers to seeking the peach [Peach Blossom Spring] to escape the oppression of the Qin dynasty (221-207 BC), established after the Qin state vanquished all other contending states and China was unified and ruled by the tyrannical First Emperor. The idea of Peach Blossom Spring, a village of peace and immortality, was a particularly comforting one in 1644 when the Ming dynasty had collapsed, China was in turmoil and once again foreign Manchu invaders were poised to take over the the Middle Kingdom. Thus not only on porcelain, but also in poetry and in paintings, such as that by Fan Qi dated AD 1646 in the Metropolitan Museum of Art,[41] Peach Blossom Spring was a favourite subject. It was also seen as "locus classicus of the ideal of the garden as timeless paradise",[42] and thus very influential in another important area of Chinese culture.

One of the frustrations of studying the narrative scenes on 17th and 18th century porcelains, is that in many instances it is clear that a particular historical event or fictional scene is being depicted, but one cannot identify it. The current author has, for instance, been unable so far to identify the subject of the decoration on an elegant rouleau vase (no. 29). This is particularly vexing as the same, or similar, subject appears on a number of other vases of the Kangxi period. In each case the central figure is obviously a person of some consequence and is dressed in the robes of a high-ranking official. He is waited-upon by a number of female attendants, who hold his fly whisk and sword, as well as serving him refreshements. The official is receiving a guest, dressed in scholar's robes, while his male attendants look on. As on the vase in this exhibition, the audience normally takes place on a terrace, in front of a screen, on which is painted a turbulent seascape. On the rouleau vase the eaves of the building together with floating clouds form the upper frame for the tableau, while rocks and plantain leaves provide framing at the sides. The same subject appears, with only slight re-arrangement of the figures, on a vase with bulbous body, long neck and slightly everted mouth in the Butler family collection. The Butler vase, has been dated to the period c. 1670-90.[43]

Thus, although our knowledge of the wares of the late Ming and early Qing period has considerably expanded in recent years, there is still much scope for further research. This is the richest period for narrative representation on Chinese porcelain and will indubitably prove a rewarding subject for future study.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

R.M. Barnhart, Peach Blossom Spring: Gardens and Flowers in Chinese Painting, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 1983

Sir M. Butler et al., Seventeenth-Century Chinese Porcelain from the Butler Family Collection, Alexandria, Virginia, 1990

Christie's Amsterdam, The Vung Tau Cargo: Chinese Export Porcelain (sale catalogue), Amsterdam, April 1992

J.B. Curtis, 'Markets, Motifs and Seventeenth-Century Porcelain from Jingdezhen', The Porcelains of Jingdezhen (R. Scott ed.), London, 1993, pp 123-49

J.B. Curtis, Chinese Porcelains of the Seventeenth Century: Landscapes, Scholars' Motifs and Narratives, University of Washington Press, Seattle and London, 1995

Fung Ping Shan Museum, Ceramic Finds from Jingdezhen Kilns, University of Hong Kong, 1992

C.J.A. Jörg, Oosterse keramiek uit Groninger kollekties, Groningen, 1982

C.J.A. Jörg, De Hatcher schenking: Chinees export porselein uit een wrak in de Zuid-chinese Zee 1640-1645, Groningen, 1984

C.J.A. Jörg, 'Chinese Porcelain for the Dutch in the Seventeenth Century: Tradin Networks and Private Enterprise', The Porcelains of Jingdezhen (R. Scott ed.), London, 1993, pp183-205

S. Little, 'Narrative Themes and Woodblock Prints in the Decoration of Seventeenth-Century Chinese Porcelains', Seventeenth-Century Chinese Porcelains from the Butler Family Collection, Alexandria, Virginia, 1990

M. Medley, 'Organisation and Production at Jingdezhen in the Sixteenth Century', The Porcelains of Jingdezhen (R. Scott ed.), London, 1993, pp 69-82

Percival David Foundation, Qing Enamelled Wares: Section 2, London, Revised edition 1991

Rijksmuseum Amsterdam, The Ceramic Load of the 'Witte Leeuw' (1631), Amsterdam, 1982

M. Rinaldi, Kraak Porcelain: A Moment in the History of Trade, London, 1989

D.F. Lunsingh Scheueleer, Chinese Export Porcelain: Chine de Commande,London, 1974

R. Scott (ed.), The Porcelains of Jingdezhen, Colloquies on Art & Archaeology in Asia No. 16, Percival David Foundation, London, 1993

R. Scott & R. Kerr, Ceramic Evolution in the Middle Ming Period: Hongzhi to Wanli (1488-1620), Percival David Foundation, London, 1994

C. Sheaf & R. Kilburn, The Hatcher Porcelain Cargoes: The Complete Record, Oxford, 1988

C. Shangraw & E.P. Von der Porten, The Drake and Cermeño Expeditions' chinese Porcelains at Drakes Bay, California 1579 and 1595, Santa rosa and Palo Alto, 1981

C.L. Van der Pijl-Ketal & Dumas, Fortune de Mer a l'Ile Maurice, Paris,

Footnotes

[1] R. Scott & R. Kerr, Ceramic Evolution in the Middle Ming Period: Hongzhi to Wanli (1488-1620), Percival David Foundation, London, 1994.

[2] J.B. Curtis, Chinese Porcelains of the Seventeenth Century: Landscapes, Scholars' Motifs and Narratives, University of Washington Press, Seattle and London, 1995.

[3] M. Butler et al., Seventeenth-Century Chinese Porcelain from the Butler Family collection, Alexandria,Virginia, 1990.

[4] R. Scott (ed.), The Porcelains of Jingdezhen, Colloquies on Art & Archaeology in Asia No. 16, Percival David Foundation, London, 1993

[5] Fung Ping Shan Museum, Ceramic Finds from Jingdezhen Kilns, Hong Kong, 1992, nos. 28-9.

[6] ibid., p. 51.

[7] Rijksmuseum Amsterdam, The Ceramic Load of the 'Witte Leeuw' (1631), Amsterdam, 1982.

[8] C.L. Van der Pijl-Ketal and Dumas, Fortune de Mer a l'Ile Maurice, Paris, 1981.

[9] C. Shangraw and E.P. Von der Porten, The Drake and Cermeño Expeditions' Chinese Porcelains at Drakes Bay, California 1579 and 1595, Santa Rosa and Palo Alto, 1981.

[10] C.J.A. Jörg, De Hatcher schenking: Chinees export porselein uit een wrak in de Zuid-chinese Zee 1640-1645, Groningen, 1984.

[11] C. Sheaf and R. Kilburn, The Hatcher Porcelain Cargoes: The Complete Record, Oxford, 1988.

[12] Christie's Amsterdam, The Vung Tau Cargo: Chinese Export Porcelain, Amsterdam, April 1992.

[13] ibid., lots 615-8

[14] ibid., lots 40-2.

[15] ibid., lot 793

[16] M. Medley, "Organisation and Production at Jingdezhen in the Sixteenth Century", The Porcelains of Jingdezhen, (R. Scott ed.), Percival David Foundation, London, 1993, p. 79.

[17] Percival David Foundation, Qing Enamelled Wares: Section 2, London, Revised edition 1991, p. 46-7.

[18] M. Medley, op. cit., p. 77.

[19] See the Wanli example illustrated by M. Medley, op. cit., p. 77, pl. 9

[20] Christies, op. cit., lots 810-27.

[21] See the incised decoration on the Ding ware meiping in the Percival David Foundation, illustrated in: R. Scott, Imperial Taste: Chinese Ceramics from the Percival David Foundation, Los Angeles County Museum, 1989, p. 25, no. 5.

[22] op. cit., lots 179-80.

[23] C.J.A. Jörg, "Chinese Porcelain for the Dutch in the Seventeenth Century: Trading Networks and Private Enterprise", The Porcelains of Jingdezhen, Percival David Foundation, (R. Scott ed.), London, 1993, p. 184.

[24] ibid., p. 186.

[25] J. Ayers & R. Krahl, Chinese Ceramics in the Topkapi Saray Museum Istnabul, Vol. III, Sothebys/Philip Wilson, London, 1986, p. 1019, No. 2181

[26] Maura Rinaldi in Kraak Porcelain: A Moment in the History of Trade, London, 1989, pp 112-3 gives a somewhat broader time span of 1635-50 for these dishes.

[27] See M. Medley, The Chinese Potter: A Practical History of Chinese Ceramics, Phaidon, London, 1976, p. 228, Fig. 176 (PDF C645)

[28] C.J.A. Jörg, Oosterse keramiek uit Groninger kollekties, Groningen, 1982, pp 44-5, no. 60.

[29] D.F. Lunsingh Scheueleer, Chinese Export Porcelain: Chine de Commande, London, 1974, pls 45-6.

[30] C.J.A. Jörg, 'Chinese Porcelain for the Dutch in the Seventeenth Century: Trading Networks and Private Enterprise', The Porcelains of Jingdezhen (ed. R. Scott), Percival David Foundation, London, 1993, p. 186

[31] A translation of the poem by Yang Xianyi and Gladys Yang appears in Poetry and Prose of the Tang and Song, Panda Books, Beijing, 1984, pp 109-15.

[32] Stephen Little, "Narrative Themes and Woodblock Prints in the Decoration of Seventeenth-Century Chinese Porcelains", Seventeenth-Century Chinese Porcelain from the Butler Family Collection, Alexandria, Virginia, 1990, p. 27.

[33] R. Scott & R.Kerr, op. cit., p. 33, no. 63 (PDF B676).

[34] This woodblock illustration is reproduced by S. Little, op. cit., p. 26, fig. 6.

[35] R. Hegel, The Novel in Seventeenth Century China, New York, 1981, p. 77.

[36] I am grateful to Grace Gray for translating both these inscriptions.

[37] This is a reference to Qin Shi Huangdi, the First Emperor of China, who was a cruel tyrant.

[38] Part of the same inscription also appears on a dish belonging to the Butler family illustrated in Julia Curtis' exhibition catalogue Chinese Porcelains of the Seventeenth Century, op. cit., pp 74-5, no. 21.

[39] C. Birch (ed.), Anthology of Chinese Literature from Early Times to the Fourteenth Century, New York, 1967, pp 167-9.

[40] ibid.

[41] R.M. Barnhart, Peach Blossom Spring: Gardens and Flowers in Chinese Painting, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 1983, p. 12, no. 1.

[42] ibid. p.15

[43] Seventeenth Century Chinese Porcelain from the Butler Family Collection, op. cit., pp 186-8, no. 130.